Almost 50 years ago, in 1974, the Combahee River Collective was founded in Boston by several lesbian and feminist women of African descent. As a sisterhood, they understood that their acts of protest were shouldered by and because of their ancestors — known and unknown — who came before them, the CRC’s name honors the military actions of abolitionist Harriet Tubman, known as the 1863 Combahee River Raid, freeing over 750 enslaved people.

Almost 50 years ago, in 1974, the Combahee River Collective was founded in Boston by several lesbian and feminist women of African descent. As a sisterhood, they understood that their acts of protest were shouldered by and because of their ancestors — known and unknown — who came before them, the CRC’s name honors the military actions of abolitionist Harriet Tubman, known as the 1863 Combahee River Raid, freeing over 750 enslaved people.

The CRC founders and frequent participants are the A-list of Black feminism’s foremothers: Cheryl Clarke, Demita Frazier, Gloria Akasha Hull, Audre Lorde, Chirlane McCray, Margo Okazawa-Rey and twins Barbara and Beverly Smith. The CRC was formed to respond to the Black Nationalist and misogynistic politics of the Black Power Movement and the exclusionary practices of white feminism.

The social upheaval of the 1960s and ’70s revealed a confluence of political struggles — the Vietnam War, Black Civil Rights, Black Power, Women’s rights and LGBTQ+ rights movements, all of which informed and ignited Second Wave Feminism. In Boston, the busing crisis and the Roxbury murders of 11 black women in 1979 added to the explosive tenor. The surge of activism and organizing was epic, and the CRC was in the mix.

Feminists Takeover

In the 1970s, the Cambridge Women’s Center was a hotbed of feminist activism. Reminders of that era are the 2016 documentary indie film “Left on Pearl,” about the feminist takeover of 888 Memorial Drive, which captures the revolutionary furor of the time, and the blue-and-white Cambridge Historical Commission placard at the intersection of Memorial Drive and Hingham Street commemorating the victory. The placard reads the following: “888 Memorial Drive. Site of a Harvard building occupied by feminists who demanded affordable housing, childcare and education, and founded the Cambridge Women’s Center, March 6–15, 1971.”

The Combahee River Collective met weekly at the Women’s Center throughout the mid-1970s. The cross-pollination of feminist groups brought together Joyce Kauffman and Barbara Smith, resulting in a decades-long friendship. Kauffman is now the proprietor of Kauffman Law & Mediation, a family law firm specializing in issues impacting the LGBTQ+ community in Boston, and a former board president of GLAD. In the ’70s, Kauffman was a member of the Boston area Socialist Feminist Organization and involved with the Cambridge Women’s Center and the Cambridge Women’s School. At the school, Kauffman co-taught a course on Marxism which Smith took.

“What Barbara remembers about the class is not so much what she learned, but how much we laughed,” Kauffman shared.

Kauffman met Smith when CRC was forming and noticed that “they were not isolationist. They worked to engage many groups and put themselves in connection with other organizations like mine, the Boston area Socialist Feminist Organization, and the Dorchester Women’s Day Group,” Kauffman recalled. All its members had been active around a range of issues before the formation of CRC.

Black Feminists

“Unlike some people who spent time in the context of the white women’s movement, I didn’t think of myself as a Black feminist until I went to the National Black Feminist Organization in late 1973. I didn’t have that difficult experience being the only black woman in a white women’s group or organization,” Barbara Smith told me.

The National Black Feminist Organization (1973–’76) in New York City was formed at the time when the single-issue agendas of Black men and white women ignored the oppressions of racism and sexism Black women confronted, naming a few. In the 1970s, NBFO was one of the earliest and most influential Black feminist organizations in Second Wave Feminism, with 10 chapters across the country. When the Boston Chapter of NBFO broke away — which Smith and Frazier established and then formed CRC — CRC became the other.

The breakaway from NBFO happened for many reasons. One of the reasons was that CRC was anti-Capitalist. “We believed socialist theory was important as we considered the material situations of Black women under capitalism. That did not appear to be a conversation taking place in the NBFO,” Frazier told The Nation Magazine in 2021. For poor Black and LBTQ women, NBFO was too myopic in its scope and in advocating for them because of its “bourgeois-feminist stance.” Because CRC was radical, grassroots and inclusive in their organizing efforts across diverse racial, class and identity groups, the CRC felt by explicitly challenging homophobia NBFO would not do enough to address the specific needs of Black lesbians in organizing as Black feminists.

The Statement

In explaining Black women’s lives as interlocking oppressions (laying the groundwork for the theory and practice of intersectionality), the “Combahee River Collective Statement” is one of the most referenced manifestos across various identity groups and movements.

The most famous line in the Statement captures CRC’s core belief: “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” Simply put, it means all systems of oppression impact Black women. If Black women’s interlocking systems of oppression were eradicated, then all other marginalized groups would be free, too. In depicting the struggles of Black women, the term “identity politics” was coined, often maligned by the Left and the Right, and used to justify separatism. Separatism is antithetical to CRC’s core actions of coalition-building. However, “identity politics” means that because Black women lived experiences in a capitalist heteropatriarchal society choke our quality of life, we have the right to determine our political agenda.

The principal writers of the Statement were Barbara and Beverly Smith and Demita Frazier. Queried in a 2014 interview if the Statement’s writers knew at the time what a seminal document they were writing, Frazier replied, “We wrote it as a collective. We crafted the Statement at a time it was ready to be heard. The content and the fullness of it came from our conscious-raising groups and testifying with one another. Although we were young and evolving, we wanted to ensure an intergenerational connection to Black and women of color feminism.”

The CRC statement was first published in Zillah Eisenstein’s anthology “Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism” in 1978.

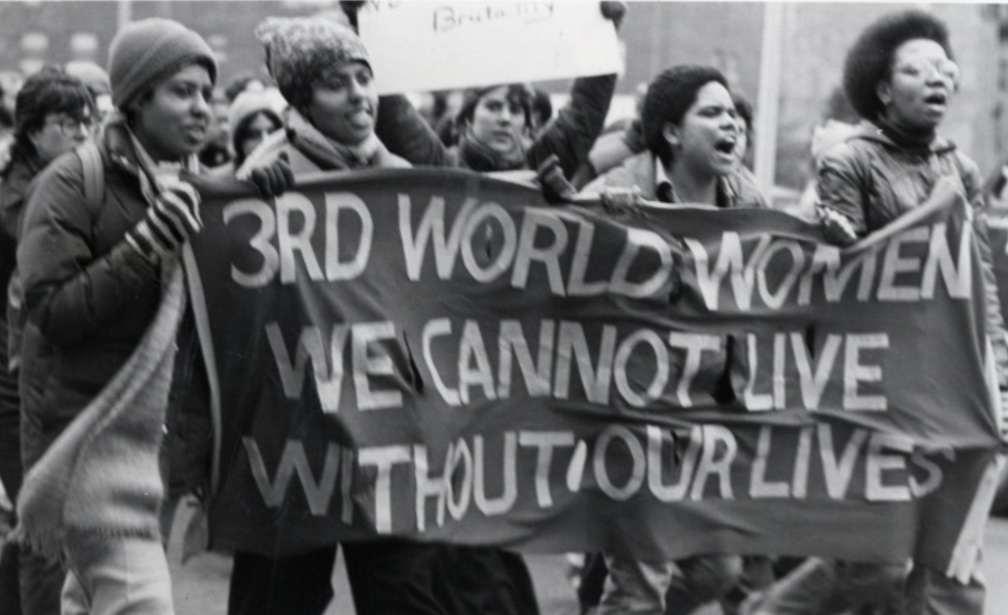

In 1979, between January and May, 11 Black women were murdered in Roxbury. Because of little local and national media coverage, the CRC wrote and distributed pamphlets entitled “Six Black Women: Why Did They Die?” drawing attention to the racialized and sexualized acts of violence against Black women.

Also, the CRC held a march, resulting in a huge community turnout. Their leadership in the crisis derived from their analysis and years of coalition-building,

Our lives as sacred texts

When the group disbanded, Smith and Audre Lorde cofounded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first publishing company run independently by women of color. As an independent press, Kitchen Table gave women of color greater control over their works, and it marketed a steady stream of books highlighting unknown talented writers. “Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology” continues to be a bestseller among women of color. It was first printed by Kitchen Press in 1983 and reprinted by Rutgers University Press in 2000.

This year marks the “Home Girls“ 40th Anniversary, and it recently won the 2023 Lee Lynch Classic Book Award from The Golden Literary Society. GLCS stated that “the groundbreaking anthology of work by Black Feminist and lesbian activists has become an essential text on Black women’s lives and writing.”

I shared with Smith that the same year “Home Girls” came out was the same year I did, too. I stopped conversion therapy and went to seminary to heed my calling to be a minister. I’ve been a decades-long ardent admirer of Smith since. “You’re not the first person to tell me they use it as a sacred text,” Smith told me. “I’m an atheist, but I have spiritual leanings not associated with any organized religion,” she said, laughing as I joined in with her. “It tickles me that people of different backgrounds find value from it.”

In the introduction to “Home Girls,” Smith wrote that she wanted the anthology to convey the meaning of Black feminism as Black women lived it and understood it. The anthology showcases 32 Black feminists from various backgrounds highlighting the similar intersectional oppressions we inescapably confront as Black women. For the first time in print, the anthology’s writings made visible Black lesbian lives, like mine, that were too often omitted from print, because much that was written about lesbianism was by and for white women.

“Home Girls” is a timeless tome because of its relatability in building a bridge for future generations. So, too, is the CRC statement.

And still, we rise!

To kick off Black History Month, Florida Governor DeSantis rolled out his list of banned Black books, with even renowned Harvard professor and PBS’s “Finding Your Roots” host Henry Louis Gates’s body of works in the lineup. I told Smith I was amused to see the CRC Statement not banned from Florida’s AP African American Studies curriculum.

“I don’t know why the Combahee remains, but it’s a primary document,” Smith says, laughing. “It’s not an individual saying this is what I think Black feminism is as an individual. It’s unsigned, and that’s on purpose. It’s a political manifesto.”

The Statement has informed the activist and political framework for Black feminist organizing in Puerto Rico and the Black Lives Matter Movement. It’s referenced in academic, political and grassroots discourses on reparations, mass incarceration, homelessness and now in the #MeToo Movement. The Statement is frequented in African American Studies, feminist studies and LGBTQ studies, all the subjects DeSantis has loudly criticized as part of “WOKE” culture.

“It’s very sharp. The Combahee River Collective Statement is very incisive. It’s clear. It’s not full of jargon at all. It’s understandable, and it has stood the test of time. People have told me so many times that it’s like it was written yesterday or last week,” Smith said. Janet Stone agreed. “Looking back, CRC Statement is the first place I now see intersectionality described clearly, “she told me. Stone is a white lesbian feminist of the ’60s and ’70s in Cambridge and coauthor of the book “Speak Up” published in 1977. “It’s foundational to women’s thinking and is just as relevant today. If I were in charge of the high school curriculum, this would be required reading nationally. “

The CRC was active from 1974 to 1980; its impact, however, is still seen today. Since Kauffman has a decades-long friendship with Smith and many of the women of CRC, I asked her where she sees CRC’s impact in Boston. “I think it trickles out,” Kauffman told me. “There’s no accident with all the organizing the Collective did. I see the direct line from that demonstration around murdered Black women in the 1970s to today. Look at how many women of color are now on the Boston City council.”

First published in Boston Spirit Magazine on March 7, 2023.